Shinto, Zen, and Japanese Furniture

As an island nation with a history of isolationism broken only occasionally by periods of trade and ideological exchange with foreign nations such as China and Korea, it is no surprise that Japanese furnishings maintained such a strong and continuous Japanese identity from antiquity until the modern era. Long after many other nations had taken up the Western style of sitting on raised chairs, the Japanese people—nobility and peasantry alike—continued to function as a floor-seated society, and their traditional furnishings reflect this. It is Japan’s strong ties with traditional Shintoism and Chinese-influenced Buddhism that give Japanese furnishings their characteristic balance of the apparently natural and the highly manicured. After a brief history of the development of various traditional furniture forms, this essay will focus on the aspects of Shinto and Zen Buddhist philosophy which have influenced not only the forms of Japanese furniture but also their deceptively simple style.

History of Forms

In the words of Koizumi, “If people know anything at all about Japan, they know that the Japanese sit on the floor” (149). This tradition has persisted since ancient times, with only occasional fads for foreign, elevated chairs that propagated among the upper classes, just as quickly to be dropped. According to Koizumi, most cultures take up chair-sitting for any of three reasons: 1) chairs lift people above the dirt, wet and cold of the ground, 2) increased height is often an indication of social standing, and 3) foreign invaders or immigrants bring chairs along with other aspects of their home culture. In Japan, the first two needs are met by raising the floor itself: many Japanese houses are built on stilts, especially those of the upper classes. The third has been negated by various periods of isolationism, combined with Japan’s easily defensible island geography. Japan had never been successfully invaded until modern times, and, while chairs have been introduced on multiple occasions, they always arrive out of context, unaccompanied by the people who are accustomed to living with them. (Koizumi, 149-150).

Thus, Japan has miraculously maintained its floor-seated culture from ancient times, and the furniture forms that befit this lifestyle are, not surprisingly, unique from the chair-seated forms that most of the Western world uses. The Japanese forms include very low tables for eating, reading and writing; standalone armrests for leaning on while sitting on thin mats; and, instead of elevated bed frames, low mats on which to sleep.

Japan may also be noted for its distinctive shinden and shoin architecture styles from the Heian through the Momoyama period. Homes built in these styles are large, open-walled pavilions which are split into usable, private spaces using screens and curtains. Because of a relative lack of permanent walls, these spaces could be rearranged for different purposes, and most furniture was designed to fold up or stack easily for storage. Most items were kept in moveable trunks and boxes, rather than permanent built-in closets, to facilitate easy rearrangement of the home for any purpose. This, too, contributed to the sleeping mat which could be folded up and stored every morning, and many other furniture forms such as a plethora of tansu chests and small, purpose-dedicated boxes, small bon trays which were used as individual place settings for meals (large, shared tables were reserved for special banquets) and a multitude of portable tsuitate screens, folding byobu screens, noren doorway curtains, and even portable hibachi braziers.

In the modern era, Japan has finally begun to take up Western forms, including chairs, elevated tables, and other large and permanent fixtures. However, traditional aesthetics and values still permeate these forms.

Aesthetic Philosophy

Much of the values apparent in the way the Japanese have chosen to build and decorate furniture can be traced to two religions: native Shinto, and Chinese-influenced Zen Buddhism, especially the tea ceremony.

Shintoism

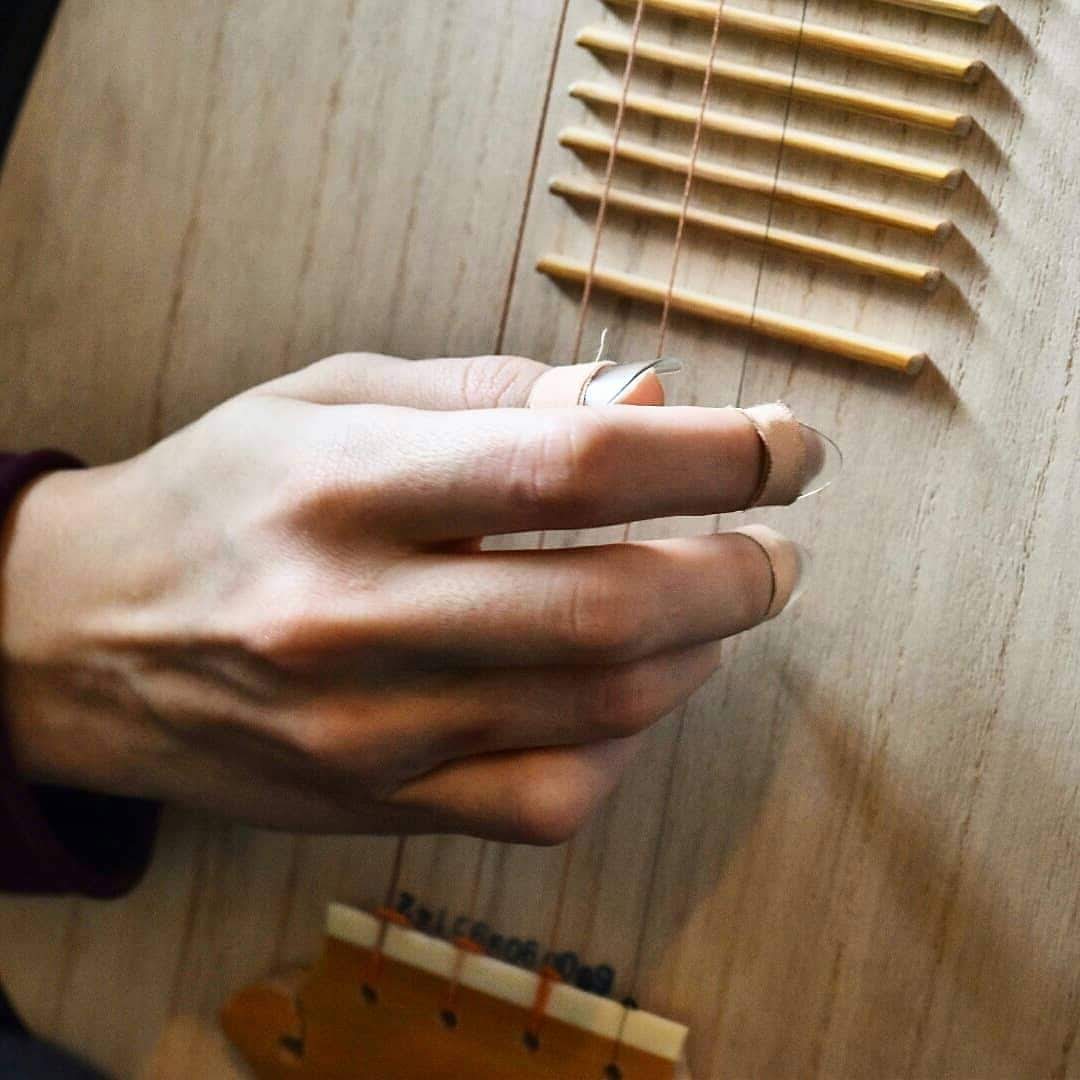

A central tenet of Shintoism is the worship of kami or the spirits that inhabit people, places, and inanimate objects, including trees, stones, and other natural phenomena. This reverence for nature deeply influences the Japanese craftsmen who seek to give trees and their kami a new life through the objects that they create with the wood. Influential craftsman George Nakashima illustrates:

A mature tree has witnessed much. In complete silence it stands immobile, a god consciousness. It is a moving experience to walk through the forest alone, to recognize each tree as a divine body, to pass in its presence day after day with a growing understanding (105). […] The tree’s fate rests with the woodworker. In hundreds of years its lively juices have nurtured its unique substance. A graining, a subtle coloring, an aura, a presence will exist this once, never to reappear. It is to catch this moment, to identify with this presence, to find this fleeting relationship, to capture its spirit, which challenges the woodworker (113).

Respect for the tree gives Nakashima and others a respect for the wood. Lumber is cut so as to minimize waste and maximize the character and beauty of each board. Broad surfaces are finished to a mirror polish. Many pieces are finished in a way to accent the beauty and grain of the wood itself, either with a clear lacquer or by leaving the wood completely unfinished. This love of plain, unfinished wood, even among the upper classes is uniquely Japanese (Koizumi, 12-13), and associated with purity, a Shinto value. Strong joinery is used to create lasting objects that will preserve the spirit of the tree for as long as possible. This respect for the tree also accounts for the Japanese style of leaving the natural edge of boards intact, whether on the edge of a table, as Nakashima is famous for doing, or on the surfaces of architectural posts and beams (Koizumi, 151) as in the Tokonama alcove of a tea room.

Zen and Tea Ceremony

Zen Buddhism, and its associated tea ceremony, came from China and includes a mixture of Daoist and Confucian ideas. The tea ceremony quickly became a ritual practice among the Japanese elite, who purchased fine Chinese porcelain tea implements to amaze and astonish their guests. However, in the 16th century, a tea master named Sen no Rikyu popularized a new form of tea ceremony, one focused on humility and hospitality (Japanology). According to Leonard Koren, “[Rikyu’s] most enduring aesthetic triumph [was] to unequivocally place crude, anonymous, indigenous Japanese and Korean folkcraft—things wabi-sabi—on the same artistic level, or even higher than, slick, perfect, Chinese treasures” (33). Rikyu’s tea rooms were drab, mud huts with thatched roofs, always small and dark with little opportunity for natural light. They had low doors that participants had to crouch through to enter. He also made a point to use utilitarian objects instead of the highly ornamented gold and porcelain objects from China, all to emphasize humility and the host’s deference to his guests. Rikyu’s style of tea ceremony quickly became the most popular, and wabi-sabi became an enduring element of the Japanese aesthetic.

Wabi-sabi, sometimes translated as “lonesome rusticity,” is characterized by crudeness, natural materials, darkness (Koren, 28-29) and “the sheen of antiquity” (Tanizaki, 11). According to Tanizaki, “In both Chinese and Japanese, the words denoting this [sheen] describes a polish that comes of being touched over and over again, a sheen produced by the oils that naturally permeate an object over long years of handling—which is to say grime” (11). Due to the Japanese’s long history of participation in the tea ceremony, the valuation of things visibly old and decaying has become a central part of their traditional aesthetic, even outside of the tea room. This translates into a love of furniture objects which have been allowed to age gracefully.

The appreciation of darkness and mystery is another element derived from the tea ceremony. Tanizaki writes at length about the Japanese affinity for the dark, the mysterious, and the glowing in both old and new objects, and he attributes the love of dark, highly polished lacquers and gold leaf to the visual effect they give in the natural darkness created in a traditional Japanese home (or tea house), with its deep, overhanging eaves. Gold, which does not tarnish and is therefore valuable for its reflective properties, was a gleaming source of reflected light in otherwise shadowed corners. In Tanazaki’s words:

Lacquerware decorated in gold is not something to be seen in brilliant light, to be taken in at a single glance; it should be left in the dark, a part here and part there picked up by a faint light. Its florid patterns recede into the darkness, conjuring in their stead an inexpressible aura of depth and mystery (14).

Once again, Rikyu’s dark and shadowy tea ceremony has found its way into the Japanese aesthetic, even when the medium has changed to more refined and polished materials.

Zen and Discipline

Japanese Zen Buddhism and it’s Chinese progenitor Chan Buddhism were attractive to martial groups in both countries, especially the Samurai class in Japan, due to its emphasis on discipline. The tea ceremony reflects this through its highly stylized nature, in which every motion and object has its absolute correct form and place. In the same way, furniture, while designed to be mysterious and evocative of the spirit of nature, is also constructed with absolute precision, simplicity, and in many cases, is highly stylized in use. For example, in traditional samurai houses, there were three necessary shelving units for a well-ordered household, distinguished by the arrangement of open and closed spaces in each (Koizumi 87-88). Traditional houses are also designed on a rigid grid of standard-sized tatami mats, and furnishings such as screens and seats are designed to reflect these standard units.

The discipline required in Zen Buddhism encouraged patience and perfectionism (Graham, 83), which resulted in furniture that is not only beautiful, but deceptively simple looking. The complexity, precision and accuracy with which joinery (the way pieces of wood are cut to fit or bind together) is executed is a distinguishing feature of Japanese furniture. Many furniture joints are based on architectural joints, necessary for building large but stable wood-frame structures like palaces and shrines from massive timbers. Japanese furniture joints are often simply shrunken-down versions of architecture joints. Compared with Western joints, many seem overly complicated or requiring inordinate skill to execute, but what they lack in simplicity of execution, they gain in strength and apparent simplicity, as some joints must be complicated on the inside in order to present a smooth or seamless surface on the outside. Thus, Japanese furnishings are an apt metaphor for the life of the Zen Buddhist who uses them: a follower of Zen must craft the pieces of his life with discipline in order to gain his own inner strength and outer calm.

Simplicity resulting from discipline was present in not only the joinery, but the materials and surface decoration of Japanese furnishings as well. Most traditional Japanese furniture items were made from native woods and fibers, with some items made from metal or ceramic. Those wooden items produced in Japan were rarely carved. The most ornament ever exhibited on traditional items was a set of metal fittings on doors or a floral motif painted into a lacquer finish, perhaps with gold leaf, on the most luxurious of items. But in general most items were made with simple, straightforward ornamentation, if any. Altogether, the Japanese aesthetic is one of simplicity, with straight architectural lines, and a counterbalancing fondness for asymmetry (Koizumi, 12).

Conclusion

As in many other elements of Japanese culture, it is the combination of native Shinto ideas and those brought from the continent, such as Zen Buddhism, that weave the beautiful tapestry of Japanese furniture traditions. A simultaneous love of the natural and the formal, the mysterious and the ordered, the apparently organic and the highly manicured, is what makes Japanese furniture so distinctive. From the humble rush mat to the elaborately gilded and lacquered ornamental shelf, the beauty of each piece is defined by careful, disciplined attendance to bringing every detail as close to nature as possible.

Bibliography:

“Begin Japanology: Japanese Tea Ceremony.” Performance by Peter Barakan, NHK World, Begin Japanology, 2 Mar. 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=gx59Y8VFse0.

Graham, Patricia Jane. Japanese Design: Art, Aesthetics & Culture. Tuttle Publishing, 2014.

Koizumi, Kazuko. Traditional Japanese Furniture. Kodansha International, 1995.

Koren, Leonard. Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers. Imperfect Publishing, 1994.

Nakashima, George, and George Wald. The Soul of a Tree: a Woodworkers Reflections. Kodansha USA, 2011.

Tanizaki, Jun’ichiro. In Praise of Shadows. Leete’s Island Books, 1977.